Blog

Go backA Brief but Complete History of the @ sign

Deep Dives · June 10th, 2025

The familiar curly "a" was never designed by a single hand; it accreted over eight centuries of scribal shortcuts, commercial bookkeeping, industrial tooling and, finally, network engineering. Below is the long arc - from quills to Unicode - in plain English.

Monastic shorthand (12th–14th centuries)

Medieval Latin scribes wrote the preposition ad ("to / at") thousands of times per manuscript. To save parchment - and wrist strain - they collapsed the d behind the a, letting the final pen-stroke curl back over the letter. The result was a compact ligature that already looks recognisably like today's @.

Merchants adopt a pricing marker (16th century)

The earliest document that shows the symbol outside a monastery is a 1536 letter by Florentine merchant Francesco Lapi. He used it to mean "at the rate of," as in "7 amphorae @ ⅛ ducat." By the late Renaissance the mark had spread through Mediterranean trading records as a unit-price shorthand.

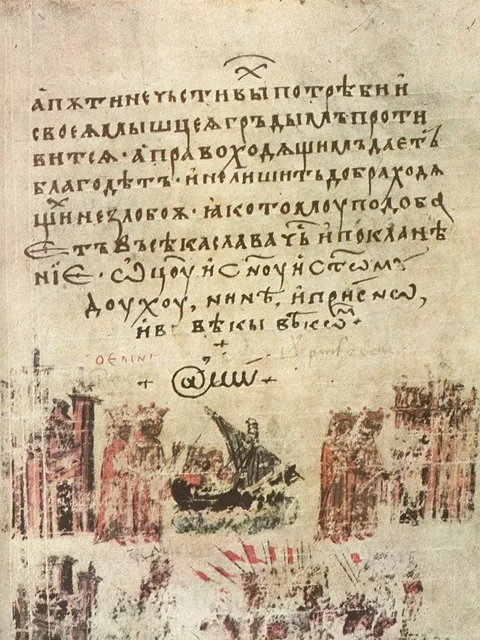

Medieval scribes created the earliest form of the @ sign as a ligature of "a" and "d" in the Latin word "ad". Here used as the initial "a" for the "amin" (amen) formula in the Bulgarian of the Manasses Chronicle, c.1345.

Medieval scribes created the earliest form of the @ sign as a ligature of "a" and "d" in the Latin word "ad". Here used as the initial "a" for the "amin" (amen) formula in the Bulgarian of the Manasses Chronicle, c.1345.

Early typewriters standardized the @ symbol's shape due to mechanical constraints of single-stroke characters. Here the keyboard from an Underwood No. 5 typewriter, circa 1900.

Early typewriters standardized the @ symbol's shape due to mechanical constraints of single-stroke characters. Here the keyboard from an Underwood No. 5 typewriter, circa 1900.

Typewriter engineers lock in the shape (late 19th – early 20th centuries)

When companies such as Underwood began casting full QWERTY keyboards in metal, they needed every printable character that accountants expected. Machining constraints favoured glyphs that could be struck with a single, continuous curve; the already curvy @ fit and the compact "one-stroke" form we still use was born.

ASCII assigns a permanent address (1967)

The American Standards Association's X3.4 committee finalised 7-bit ASCII with 95 printable characters. Slot 0x40 (decimal 64) was free, so the committee parked @ immediately before uppercase "A". That single decision guaranteed the symbol a spot on every computer keyboard - whatever its national layout - because firmware now expected it.

Email turns @ into a global separator (1971)

Working on ARPANET, engineer Ray Tomlinson needed a character that would never appear in user names to separate a local account from a remote host. He chose @ because "it just made sense" and was sitting unused on his Teletype keyboard. The moment he sent tomlinson@bbn-tenexa, the glyph became the connective tissue of digital identity.

Unicode, fonts and regional keyboards (1991 >)

Unicode simply inherited ASCII's code-point, but type designers still reinterpret the stroke width and loop tightness-compare Helvetica's compact whirl with Courier's roomy oval. Keyboard placement, however, is localised: on the US layout it is Shift + 2; on German it is Alt Gr + Q; on French AZERTY Alt Gr + 0. The symbol's coding is universal, its key-combo is not.

Ray Tomlinson, who chose the @ symbol for email addresses in 1971, forever changing its significance.

Ray Tomlinson, who chose the @ symbol for email addresses in 1971, forever changing its significance.

“@” Around the World -

a quick tour of its weirdest nicknames

| Language | How locals say “@” | Literal English meaning |

|---|---|---|

| German | Klammeraffe | “Spider-monkey” (looks like a tail hanging from a branch) |

| Hungarian | Kukac | “Worm / maggot” |

| Italian | Chiocciola | “Snail” |

| Dutch | Apenstaartje | “Little monkey-tail” |

| Danish / Swedish | Snabel-a | “Elephant-trunk a” |

| Russian | Sobaka | “Dog” (the loop is a curled-up puppy) |

| Polish | Małpa | “Monkey” |

| Hebrew | Shtrudel | “Strudel pastry” |

| French (slang) | Escargot | “Snail” (official term is arobase) |

| Finnish (slang) | Kissanhäntä | “Cat’s tail” |

Now you can order pastries, spot wildlife and talk email - all with a single glyph.

TL;DR

- Evolution, not invention: the @ is a layered palimpsest of medieval ligature, merchant bookkeeping mark, type-bar compromise and network delimiter.

- Standardisation cemented adoption: ASCII (binary slot) and email (semantic role) are the twin pillars that made the sign indispensable.

- Form follows constraint: every curve you see is a fingerprint of past technologies-from quills that couldn't lift easily, to steel typebars that had to strike once, to 7-bit code charts that could spare exactly one printable slot.

The next time you hunt for @ on your particular keyboard, you're touching eight hundred years of incremental design choices-none of which foresaw social-media handles or spam filters, yet all of which still work.