Blog

Go backRay Tomlinson, the accidental "QWERTYUIOP" & how email was born

Deep Dives · June 3rd, 2025

A midnight experiment

It is a humid summer night in 1971 inside the offices of Bolt, Beranek & Newman. Two refrigerator-sized PDP-10 computers blink in the half-light.

Ray Tomlinson is supposed to be improving CPYNET, a file-transfer tool for ARPANET. Boredom nudges him off script. He wonders: What if I could leave a note on the second computer instead of just shipping files? The question is so small it almost slips past him. History, however, has a taste for small questions.

Tomlinson - soft-spoken contractor, chronic tinkerer - leans across a console and types a single line:

QWERTYUIOP

He presses SEND. On another machine, meters away, the characters arrive. No trumpet sound, no memo, no press release - yet in that moment the world receives its very first networked email.

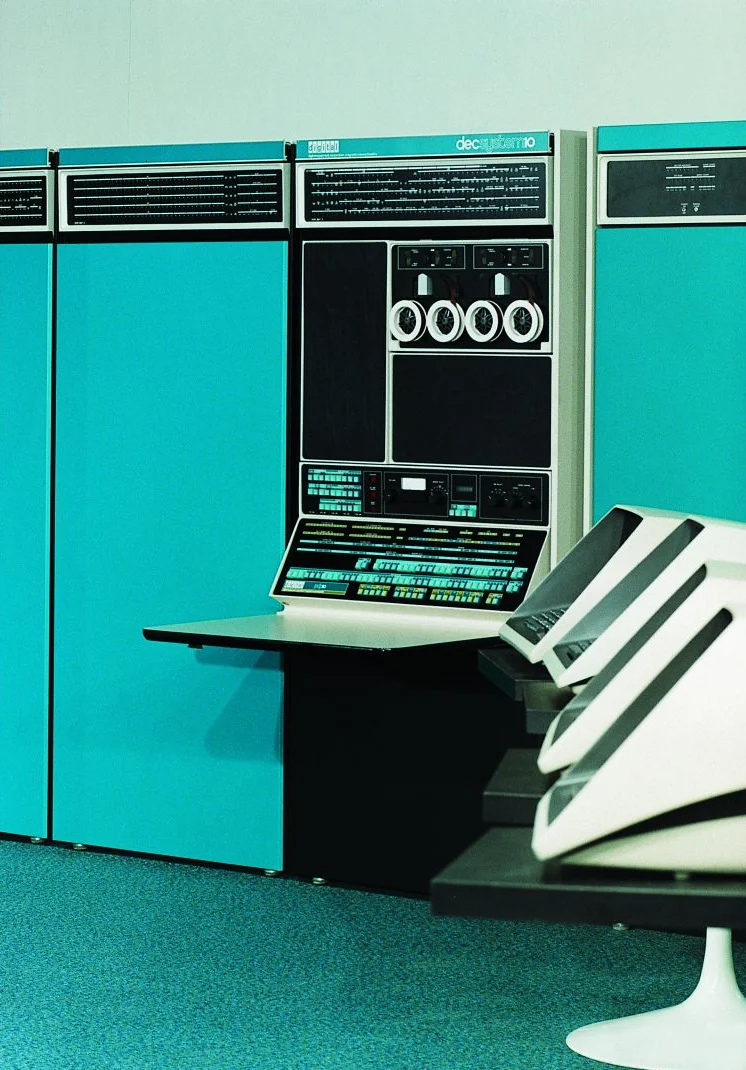

1971: DEC’s PDP-10 (born 1966) turned time-sharing from sci-fi into office reality, shoved data across the early ARPANET and even handed HP a new cash lane-before DEC itself got gulped by HP in 2002.

1971: DEC’s PDP-10 (born 1966) turned time-sharing from sci-fi into office reality, shoved data across the early ARPANET and even handed HP a new cash lane-before DEC itself got gulped by HP in 2002.

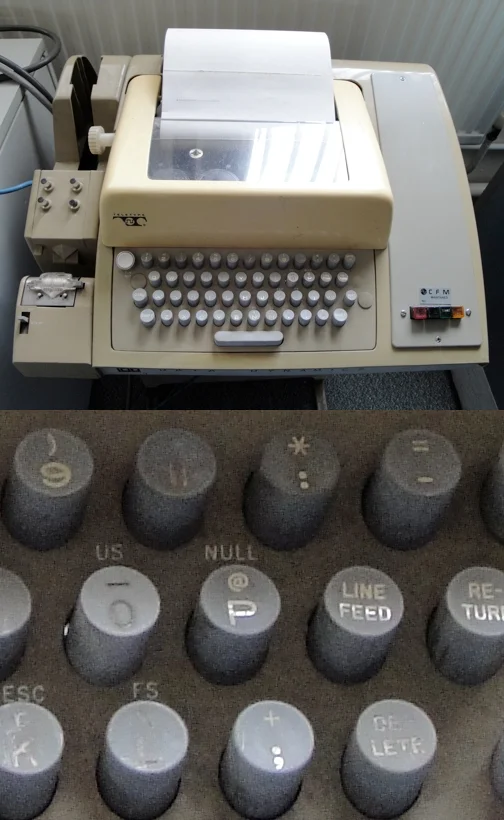

Teletype ASR-33, circa 1960s-back when the @ had to roommate with the P key.

Teletype ASR-33, circa 1960s-back when the @ had to roommate with the P key.

Choosing the "@"

To tell the machines where to deliver a message he needs a separator - user here, host there. Slashes and colons are already taken. But the @ sign is just sitting there on every ASR-33 keyboard, a symbol that merchants have used for centuries to mean “at the rate of” (think 7 widgets @ $1). Its roots go deeper still - medieval scribes scratched it as shorthand for the Latin "ad", meaning “toward/at.” In other words, the glyph was literally born to connect things.

Read further:

A brief but complete history of

the @ sign

It’s quirky, pronounceable and - as far as computer syntax goes - totally unemployed. Tomlinson taps it, shrugs and ships. Half a century later, billions of inboxes still bow to that casual midnight decision.

Why the hack stuck

- No new hardware required. ARPANET already linked the hosts; Tomlinson merely piggy-backed on existing circuits.

- Instant utility. Researchers could trade notes and code in minutes instead of waiting for punched-tape deliveries.

- Zero bureaucracy. The feature shipped before anyone could schedule a meeting to object.

Within months, informal guidelines began circulating. In 1973 they congealed into RFC 561 and the snowball kept rolling: SMTP in 1982, MIME in 1992, DMARC in 2015-layer upon layer over the original late-night hack.

The ripple effect

| Year | Milestone | Daily email volume * |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | First ARPANET mail header standard | < 100 |

| 1986 | .com addresses top 100,000 | 1 million |

| 1996 | Hotmail launches webmail | 10 billion |

| 2004 | Gmail introduces threaded view | 36 billion |

| 2025 | Global email crosses 347 billion | 347 billion |

* Approximate, pieced together from industry studies and vendor telemetry.

Behind the numbers hides a simple truth: email succeeded not because it was perfect, but because it was good enough and open to everyone. Any computer that could speak the protocol joined the conversation. In an industry addicted to proprietary kingdoms, that openness became email's moat.

Technical debt, yes - but also they’re daily reminders that the modern inbox sits atop half a century of quick wins and clever hacks and that ideas born in a lab at 2 a.m. can outlive their creators.

Ghosts in today's inbox

- Trust first, verify later. Early ARPANET assumed every node was friendly. Spam, spoofing and CEO-fraud thrive on that baked-in naivety. Every new standard - SPF, DKIM, DMARC, even ARC - is basically duct tape over a 1971 trust fall.

- Seven-bit ASCII forever. Emoji gymnastics, odd MIME wrappers and right-to-left-text glitches all exist because the original line printer couldn’t imagine sushi emojis or Ukrainian. We’re still asking 21st-century bytes to tip-toe through a 128-character museum.

- Store-and-forward latency. Messages still hop from relay to relay like 1970s registered mail. Great for resilience; painful when you’re staring at a spinning “syncing…” badge on 5G.

- Reply-all culture. Reply-all culture. The “CC:” header was designed for a handful of grad students, not four thousand bored employees smashing Reply All to say “unsubscribe.” Corporate inboxes now host reply-all storms like digital hurricanes.

- Header haystacks. Each email carries a forensic novel of Received: lines, custom X-headers and arcane timestamps. Good luck reading them; attackers hide trackers and exploits in the clutter.

- Attachment anachronism. We still bolt hefty files onto emails because 1970s FTP was clunky. Now every mailbox drags orphaned 10-MB PowerPoints like cosmic space junk.

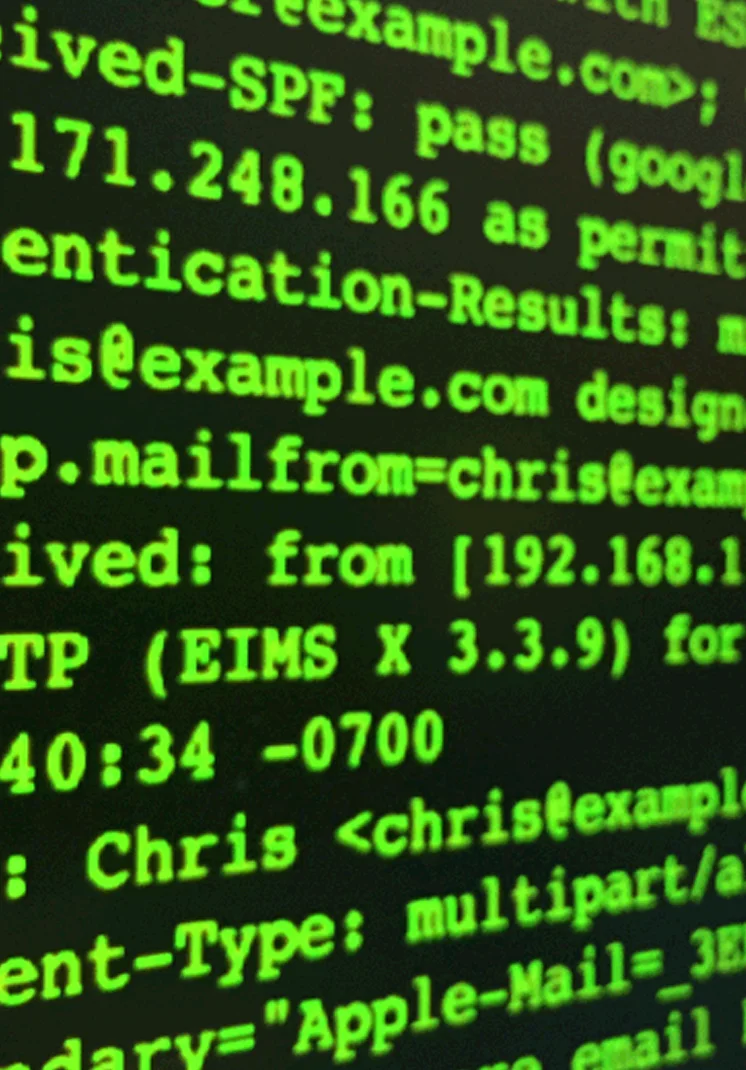

Matrix-green slab of raw email headers - “Received: from...,” SPF mumbo-jumbo and other undead metadata hitching a ride in every message since the ’70s.

Matrix-green slab of raw email headers - “Received: from...,” SPF mumbo-jumbo and other undead metadata hitching a ride in every message since the ’70s.

Myth-checking the 'QWERTYUIOP' legend

Tomlinson later admitted he can't swear that the top-row keystroke was the first message; it might have been gibberish or "TEST." Historians hunted for logs and found none. Yet the myth survives because it captures the casual spirit of the moment: the world shifted before anyone realised it had.

Ron Burgundy processing the news that email has outlived every “inbox killer” since 1971.

Ron Burgundy processing the news that email has outlived every “inbox killer” since 1971.

Why email refuses to die

The tech world has tried for decades to kill the inbox - group chat, social DMs, collaboration hubs, you name it. Yet the “Send” button keeps winning bar - bets because it solves more edge-cases than its rivals even attempt. A few of the big reasons:

- Identity anchor. An email address doubles as a passport: logins, password resets, 2-factor prompts, parcel notifications - everything still funnels back to that.

- Permanence. New messaging apps vanish, companies fold, phones drown, but IMAP folders migrate with a single export. Email is the cockroach of data formats - in the best way.

- Universal reach. One protocol, every demographic: your nan, your lawyer, the prime minister’s press office, a random open-source maintainer. No other channel bridges all silos.

- Vendor-agnostic openness. SMTP/IMAP/JMAP are public specs; nobody holds a master switch. Slack can rug-pull features, WhatsApp can geo-block, but email’s decentralised mesh keeps humming.

- Resilience at scale. Store-and-forward plus queued retries means messages usually arrive - even over satellite links or disaster-zone networks where real-time chat falls apart.

- Legal & regulatory comfort. Courts, auditors and compliance teams treat email like digital certified mail. Screenshots of a Slack thread rarely meet evidentiary standards.

- Low friction, low cost. Any device with a screen and a TCP/IP stack can send email; that barrier of entry fuels adoption in emerging markets and on decade-old hardware.

Until another medium checks all of those boxes at once - and does so without locking users inside one corporation’s walled garden - email will keep outrunning every “email killer” headline.

TL;DR

Send an email today and you’re leaning on a half-century chain of midnight hacks, last-minute glyph choices and accidental standards. That chain reminds us:

- Tiny experiments scale. Tomlinson just wanted to skip a hallway walk; the rest of us got an internet backbone.

- Openness beats polish. Protocols that anyone can implement win over shinier but gated systems-every single time.

- Old choices echo. The ‘@’, seven-bit ASCII, even “CC:” still shape how we communicate. Your quick-n-dirty patch on a Friday could be someone’s dependency in 2075.

So, the next time you hover over the Send button - whether it’s a launch announcement or a “hey, lunch?” ping - remember you’re contributing to a living archaeological layer. Write like someone might dig it up in 50 years.

Ray Tomlinson (1941 – 2016) - Amsterdam-born BBN coder who hit “@” in ’71, stitched two PDP-10 programs together and accidentally gifted the planet email.

Ray Tomlinson (1941 – 2016) - Amsterdam-born BBN coder who hit “@” in ’71, stitched two PDP-10 programs together and accidentally gifted the planet email.